Charles Schultz

The Creator of Charlie Brown and Peanuts

By: Curt Brown, Star Tribune

Published December 2, 1997 SCHVARM

Approaching his 75th birthday celebration Wednesday, Charles

Monroe Schulz could wax nostalgic about growing up as a barber's

kid in the Twin Cities.

But forget about the back-yard ice rinks and the rumbling

streetcars. Schulz would rather be frank.

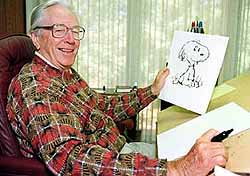

"Those were some terrible times," he said the other day, after

his admittedly shaky hand sketched out yet another Sunday

"Peanuts" comic strip. More than 200 million readers will see his

work today in 2,400 newspapers in 68 countries.

But the $20 million a year that Schulz grosses today can't erase

the memory of too many pancake-dinner yesterdays. He always

thought his parents really liked pancakes; now he realizes it was

all they could afford.

From the studio in his sumptuous Santa Rosa home about an hour

north of San Francisco, Schulz recently recalled the Depression,

the rejections and "those early defeats you never get over."

School is war

Schulz was a 6-foot-tall, 136-pound outcast at St. Paul Central

High School, and his cartoons were deemed unworthy for the senior

yearbook in 1940.

"I don't know which was worse - the Army or Central High School,"

Schulz said. "I was a bland, stupid-looking kid who started off

bad and failed everything and hated the whole time.

"Then my art teacher asked me to draw some school scenes for the

annual. I was delighted and waited anxiously the last couple days

of school until the yearbook came out - with none of my cartoons."

His mother, Dena, died of cancer just as her only child turned

20. And Schulz's father, Carl, nearly lost his 35-cents-a-cut,

three-chair Family Barbershop during the Depression.

"At one point, he was seven months behind on the rent," Schulz

said. "I asked him once how in the world he could keep that up,

and he said the man who owns the building can't find anyone with

money to rent the place, so he's glad for what he gets."

Then there was Schulz's love life. As a fledgling cartoonist at

what is now Art Instruction Schools in Minneapolis, Schulz fell

in love with a red-haired co-worker named Donna Johnson and

promptly proposed.

She said: "No" and married a Minneapolis firefighter named Al

Wold instead. Today, Al and Donna are celebrating his retirement

on a vacation in England. Their 50-year anniversary is coming up

in 2000.

"I loved that little girl but her mother convinced her I would

never amount to anything," said Schulz, who immortalized Donna as

the red-haired girl who frustrates his alter ego, Charlie Brown,

as much as any kite-eating tree or quick-yanking football holder

ever could.

"You never do get over your first love," Schulz said. "More than

having your cartoons rejected or three-putting the 18th green,

the whole of you is rejected when a woman says: `You're not worth

it.' "

Birthday wish

Schulz plans to celebrate his 75th birthday much like the

previous few: golf and dinner with his friends and some cake with

his second wife, Jeannie, and his five grown children.

Schulz does have a secret birthday wish, though.

"My goal in life," he said, "is to meet Andrew Wyeth" - the

80-year-old Pennsylvania painter who won the 1990 Congressional

Gold Medal, one of America's most highly regarded living artists.

"I'll never be an Andrew Wyeth, and that's kind of sad," Schulz

said. "I wish what I did was fine art, but I doubt it is. It's

well researched and authentically drawn, but I do not regard what

I am doing as great art.

"Comic strips are too transient. Art is something so good it

speaks to succeeding generations. . . . I doubt my strip will

hold up for several generations to come."

Not that he's about to stop producing. After 47 years, Schulz

still draws his own strip every day without the drafters and

creative teams employed by some of his younger colleagues.

"Some days, I just look at my yellow attorney's pad all day and

think of nothing, but today I finished two Sunday strips," he said.

His hands are getting shaky, but when the computer reduces his

drawings, the quivering lines are hard to detect.

"I kind of prop one hand against the other," he said. "And it all

comes a little slower."

He's 10 years past a typical retirement age, but has no plans to

pull the plug on his moon-faced characters with their childish

bodies and grownup anxeties.

"I'll keep drawing as long as I stay well - there's nothing else

I know how to do," he said. "I enjoy - if you can use that word -

drawing just like a pianist plays piano, a poet writes poems and

a painter does watercolors. They do it because life wouldn't mean

anything if they didn't. It's my life."

Largely ignored locally

Of all the Twin Cities' native artistic sons - from F . Scott

Fitzgerald to LeRoy Neiman, from Prince to Garrison Keillor -

Schulz might have put the biggest imprint of all in the

collective psyche of American pop culture.

Through Linus, he gets credit for popularizing the term,

"security blanket." His "Happiness is a warm puppy" line became

'60s bumper-sticker fodder. He's inspired umpteen TV specials and

a Broadway play, not to mention an amusement park at the Mall of

America.

"But, incredibly, the state and the Twin Cities largely ignore

him," said Dave Mruz, a Minneapolis art historian and cartoon

buff. "It's unbelievable that his hometown has no permanent

statues, no displays at the History Center, nothing to recognize

him."

Well, almost nothing. Schulz's memorial plaque - along with those

honoring Fitzgerald , aviator Charles Lindbergh, hockey coach

Herb Brooks and politician Hubert Humphrey - recently moved seven

blocks from St. Paul's old train depot to Town Square. And

another plaque hangs in the hallway of Central High School's Hall

of Fame.

"Nobody would have believed that when I went to school," he said.

"At our 25th reunion, I was on the list of people nobody knew

what happened to."

The last time he visited Minnesota, in 1994, Schulz went up to

the apartment above O'Gara's Bar and Grill at Snelling and Selby

Avs. where he lived as a child, and he sketched a Snoopy on the

wall. Next to the oversized snout of a beagle known worldwide,

Schulz drew a shaky little heart.

"I suppose we all go through phases in our lives," Schulz said.

"I don't know that they were the best years. There were some good

ones and some nasty ones. The streetcar track no longer runs out

front and it's kind of sad the barbershop's not there. But that's

home, nevertheless."

Charles M. Schulz

A Minnesota chronology

Nov. 26, 1922/ Charles Monroe Schulz is born in Flat No. 2 at 919

Chicago Av. S. in Minneapolis, the only child of St. Paul barber

Carl Schulz and his wife, Dena.

1928/ Schulz's childhood home is at 1604 Dayton Av. in St. Paul.

As a kindergartner at Mattocks School, Schulz draws a man

shoveling snow with palm trees in the background and his teacher

says: "Charles, someday you'll be an artist." (Relatives had

recently moved to California and sent word of palm trees.) Schulz

later attends Richard Gordon Elementary School.

1934/ The Schulzes are given a black and white mutt. "Spike was

totally uncontrollable. He loved to ride in my father's car,

though, so when he'd get loose, the only way you could get him to

come would be to honk the horn. Spike and Snoopy have similar

markings." 1936/ Schulz enters St. Paul Central High School,

where he says he routinely flunked classes. "I even flunked

dating, which was understandable, because who'd have gone out

with me?"

By this time, his family moves to 473 Macalester St. in St. Paul.

He works as a caddie at Highland Park Golf Club.

1941/ Schulz takes cartooning-by-mail courses from the Federal

Schools, a Minneapolis correspondence program. His instructor,

Frank Wing, gives him a C-plus in Division 5: "Drawing of

Children."

1943/ Drafted into the Army, he serves as a infantryman, staff

sergeant and machine gunner, although he never gets too close to

the European front lines.

1945/ Schulz earns $85 a week as an instructor at the Federal

Schools, now known as Art Instructions School. In the evenings,

in the apartment he shared with his father over what is now

O'Gara's bar in St. Paul, he letters other cartoonists' comics

for Timeless Topix, owned by the Roman Catholic Church.

1947/ He sells a cartoon feature called Li'l Folks to the St.

Paul Pioneer Press. It runs weekly for two years.

1948/ Schulz sells a panel to Saturday Evening Post for $40 of a

young boy reading a book in a big easy chair. "I wanted to be

somebody. All of us want to be somebody. I remember so well that

first night I was able to say: `I am a cartoonist.'"

June 1950/ He boards a train from St. Paul to New York with a

portfolio of cartoons. Signs a five-year deal with United Feature

Syndicate, which calls for a 50-50 split of profits. When the

syndicate names his strip "Peanuts," Schulz hates it because, "to

me, `peanuts' means insignificant and unimportant."

Oct. 2, 1950/ "Peanuts" debuts in seven newspapers. Schulz lives

at 5521 Oliver Av. S. in Minneapolis.

1952/ Strip spreads to 40 U.S. papers and one in Japan. Schulz

teaches correspondence cartoon drawing classes and has a studio

at the Bureau of Engraving, 500 S. 4th St.

1958/ With "Peanuts" now in 355 U.S. papers and 40 foreign

dailies, Schulz moves from his home at 112 W. Minnehaha Pkwy. to

Santa Rosa, Calif. He builds a 12-room house and studio on four

acres with the address One Snoopy Place.

Fun facts about

Charles M. Schulz

Sniffy and the Red Baron?

Originally, Schulz was going to name the adorable beagle in his

strip "Sniffy," which he modeled after his childhood mutt Spike.

"I was walking around the Powers department store in Minneapolis

and there was a little magazine stand. I saw a comic with a dog

named Sniffy and thought, `Oh, no, there goes my dog's name.'

Then I remembered a long time ago when my mother said: `If we

ever have another dog, we should name it Snoopy.' "

Real-life inspirations

In his early cartoonist days at the Art Instruction Schools in

Minneapolis, Schulz worked with people named Frieda Rich and

Charlie Brown, who went on to become a probation officer for the

Hennepin County Juvenile Detention Center. Schulz says he has

transferred many of his own early frustrations into his main

character, Charlie Brown. "Oh, definitely, the poor guy," Schulz

said. "I worry about almost all there is to worry about. And

because I worry, Charlie Brown has to worry." Both Frieda and

Charlie have died, but another old Minneapolis pal, Linus Maurer,

lives in southern California and talks with Schulz occasionally

by phone.

Heckuva bird bath

As a childhood St. Paul Saints hockey fan and an ice skating

aficionado, Schulz still skates frequently in Santa Rosa, where

the city's ice arena fell on hard times in 1968. "The arena

wasn't in great shape, and when I heard it was going to close, I

said, `I wish there was something we could do about it,' " Schulz

said. So, in 1969, Schulz built the Redwood Empire Arena, an

architectural gem a block from his studio. That's one of the

reasons he was inducted into the U.S. Hockey Hall of Fame.

For more

To learn more about Schulz, read "Good Grief! A Biography of

Charles M. Schulz," by Rheta Grimsley Johnson.

Back To Charlie Brown, Snoopy & Peanuts Index

For Really Cool Pet Related Gift Items

and Gifts for Pets Check Out:

Our Pet Gift Shop Here

Simply the Cutest Stuffed Plush Animals

Free Dog Care Tips

Free Cat Care Tips

Home

Copyright ©

Choose To Prosper